For the Greek farmer, climate change, growing water scarcity and prolonged drought are no longer abstract scientific notions but a hard daily reality. Climate projections foresee a 10–30% decline in rainfall by 2050, placing 30% of the country at risk of desertification. In this pressing context, efficient water management is no longer just a “good practice”; it becomes a matter of survival for the primary sector.

Yet our approach to irrigation is often reduced to a simplistic logic: the plant is thirsty, we water it. However, this view overlooks a fundamental truth: irrigation is not a simple input but one of the strongest management interventions we make in a field. Every drop we apply triggers a complex chain of physical, chemical and biological processes beneath the soil surface. The way, the frequency and the volume of irrigation can either build a fertile, resilient, living soil—or degrade it gradually into a compacted, saline and biologically depleted substrate. Globally, unsustainable agricultural practices, including poor land and water management, account for 62% of soil degradation.

The purpose of this article is to broaden our perspective, moving from the technical view of irrigation as mere water supply to a holistic, agroecological approach: how irrigation practices affect, directly and indirectly, soil quality and soil health, the agroecological environment, and how all these ultimately influence what matters most to the grower: the yield and above all, the quality of the harvest.

Physical and chemical impacts on soil

The irrigation methods and practices we choose have immediate—and often dramatic—consequences on soil structure and chemistry. These effects, though initially subtle, accumulate over time and determine the long-term fertility and productivity of the field.

Erosion: the silent loss of fertility

Water erosion removes the precious topsoil under the force of moving water. Traditional methods such as flood, border, or furrow irrigation—especially on sloping ground—are particularly prone to causing erosion. When water runs rapidly over the surface, it carries away the finest and most fertile particles, including organic matter. Studies have shown that furrow irrigation can remove from 20 to 200 tons of soil per hectare annually, a loss multiple times the natural soil formation rate. This is not a mere relocation of dirt: it is the loss of the most living, nutrient-rich part of the field, leading to a gradual decline in fertility and higher fertilizer costs. In contrast, modern methods such as drip irrigation apply water slowly and directly to the rhizosphere, minimizing runoff and almost eliminating erosion risk, thereby protecting the farmer’s capital—namely, the soil itself.

Compaction: when the soil suffocates

Soil structure, i.e., how particles bind into aggregates, is vital for soil health. Good structure creates pores of different sizes, allowing air movement, water infiltration and unimpeded root growth. Excess irrigation—especially when the soil is already moist—can be destructive: water displaces air from pores, making soil particles vulnerable to compaction from machinery loads or even gravity. Compaction destroys macropores, sharply reduces aeration, impedes drainage and erects a physical barrier to root extension. Roots are forced to grow in a hostile, oxygen-deprived environment, limiting their ability to take up water and nutrients. The result is a stressed plant with reduced productivity, even when water and fertilizer are supplied generously.

Salinization: the invisible enemy in the rhizosphere

Soil salinization is one of the most insidious and serious irrigation-related risks, particularly in the Mediterranean’s dry, hot conditions and especially in coastal and island areas of Greece where water quality is often borderline. Every irrigation water—even “fresh” water—contains dissolved salts. As plants absorb water, salts remain and accumulate in the soil. Frequent, small irrigations, especially with water of elevated electrical conductivity (ECw), exacerbate the problem. Water evaporates from the surface, leaving salts behind that concentrate right where it matters most: in the root zone.

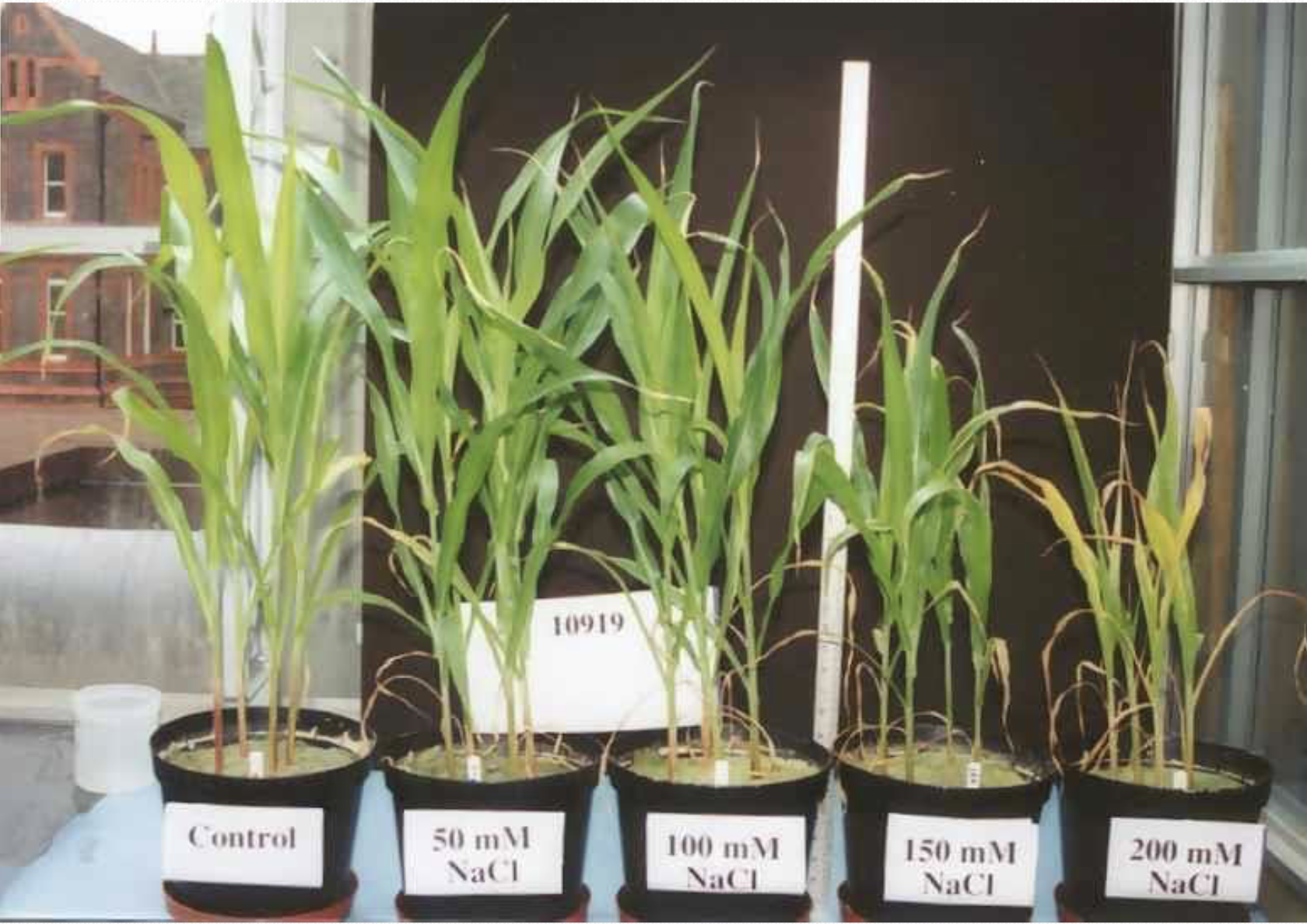

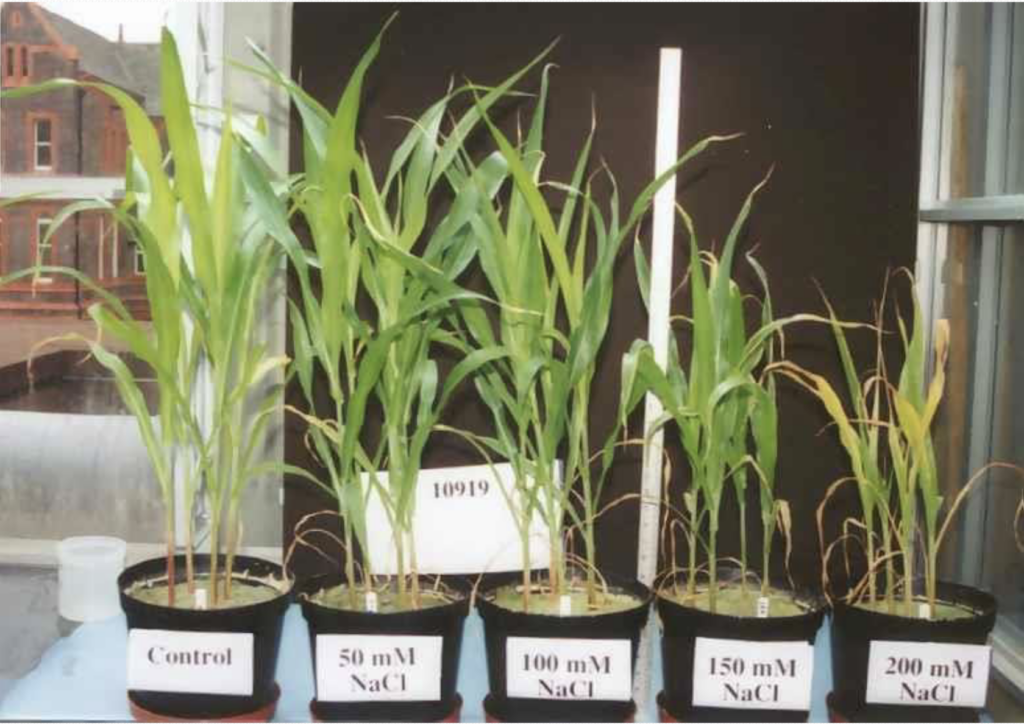

This accumulation increases the electrical conductivity of the soil solution (ECe), creating what is known as “physiological drought.” The plant, although surrounded by moisture, struggles to take up water because it must overcome the high osmotic pressure imposed by salts. The outcome is water stress and slow, reduced growth (even without visible wilting) and, in severe cases, ion toxicity from sodium and chloride which, depending on crop sensitivity, can cause significant yield losses (Fig. 1).

Nutrient leaching: the cost of excess

While small, frequent irrigations can drive salinization, over-irrigation creates a different but equally serious issue: nutrient leaching. When applied water exceeds the soil’s water-holding capacity at field capacity, the excess percolates downward, carrying with it mobile nutrients, mainly nitrate nitrogen. This is a direct economic loss for the grower and, perhaps more importantly, a pollutant of groundwater. Poor irrigation management thus converts an agricultural input into an environmental contaminant, undermining the sustainability of the entire farming system.

Key points

- Erosion: Traditional irrigation (flood, furrow) can cause major losses of fertile soil, unlike drip irrigation.

- Compaction: Over-irrigation on wet soils destroys soil structure, reduces aeration and impedes root growth.

- Salinization: Salt buildup in the rhizosphere, especially with brackish water, causes osmotic stress and lowers yields.

- Leaching: Excess irrigation leads to the loss of valuable nutrients (e.g., nitrates) and contamination of aquifers.

Effects on soil health

Beyond immediate physico-chemical changes, irrigation practices exert a deep and often underrated influence on the field’s most dynamic component: the soil ecosystem. Soil is not an inert rooting medium but a bustling metropolis of billions of microorganisms and enzymes they produce, performing vital functions in symbiosis with plants. Water management largely determines whether this living city thrives or declines

Microbiome and biochemical functionality

Soil microbial communities (bacteria, fungi, protozoa) are the unsung heroes of fertility. They recycle nutrients, decompose residues into plant-available forms and improve soil structure. Their survival and activity, however, are governed by moisture, aeration and soil chemistry – all heavily shaped by irrigation. Sharp cycles of intense drought followed by saturation – typical of infrequent, heavy irrigations – cause osmotic shock and reduce functional diversity. Seasonal drought, meanwhile, can lower microbial nitrogen and phosphorus pools by 15–20%, forcing communities to divert resources into stress tolerance rather than growth. These shifts disrupt symbioses with plants and constrain nutrient exchange in already oligotrophic soils.

Over-irrigation, on the other hand, creates anoxic conditions that alter community composition, favoring anaerobic microorganisms, many of which are pathogenic, while suppressing beneficial aerobes.

As discussed earlier, salinization is particularly toxic to microbial life. Research shows that irrigation-induced increases in salinity and alkalinity progressively reduce microbial abundance and metabolic activity. This slows critical biogeochemical processes like denitrification, and mineralization of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus, thereby reducing the natural availability of nutrients to the crop.

From microorganisms to biodiversity: a fragile chain

The impact of irrigation does not stop at the microbial level. It extends across the agroecological web, influencing soil fauna and beneficial insects. Studies report strong negative effects of irrigation (especially flooding) on beneficial arthropods such as predators, parasitoids and pollinators. Disturbing the soil environment by creating unsuitable moisture regimes can destroy habitats, refuges and food resources for these organisms, which are the farmer’s allies in biological control and pollination. Practices that promote soil health, such as reduced tillage, cover crops, and organic amendments depend on rational, targeted irrigation to succeed. Balanced moisture supports cover-crop growth, which in turn offers forage and shelter for pollinators and other beneficials, enhancing overall biodiversity and farm resilience.

The two-way relationship between organic matter and water

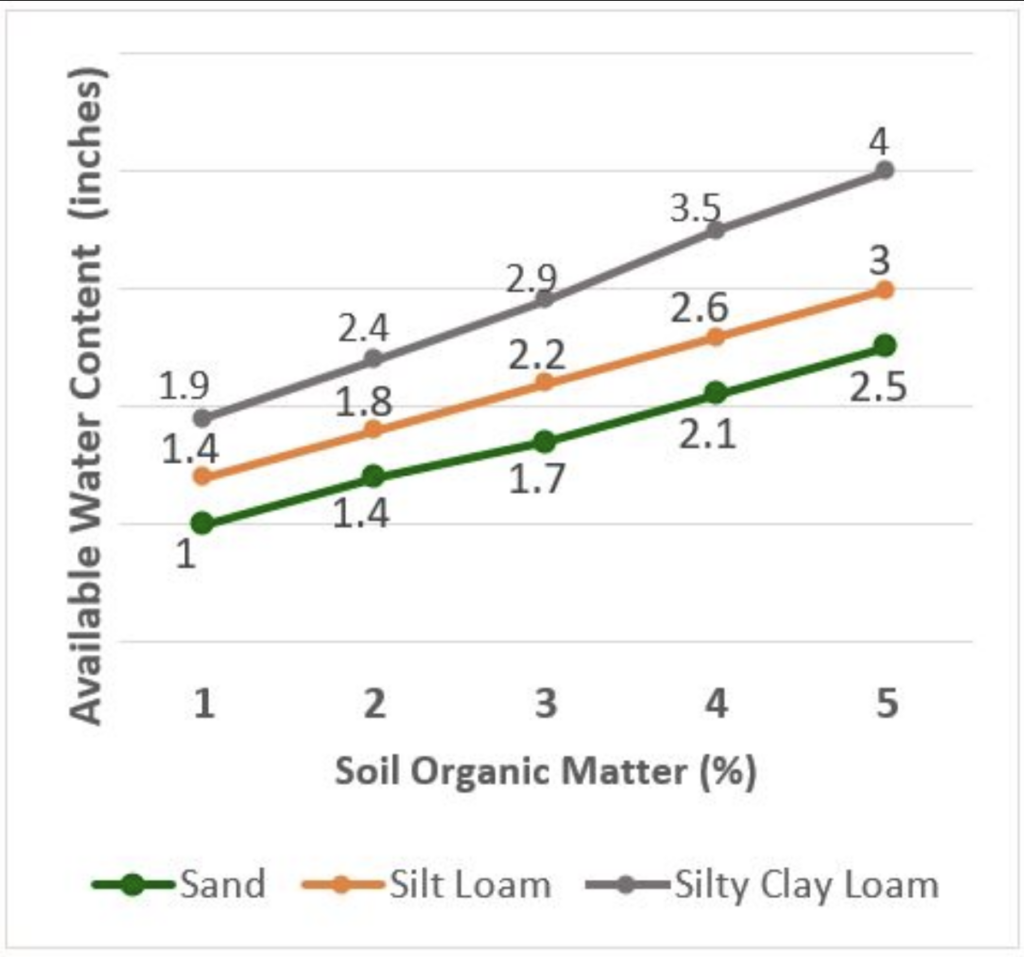

Organic matter is the heart of soil fertility, and its relationship with water is profoundly bidirectional. On one hand, sound irrigation management promotes plant growth and microbial activity, increasing biomass production (roots, residues) and its timely decomposition – processes that raise soil organic matter (SOM). On the other hand, a SOM-rich soil behaves like a sponge. Organic matter improves structure by forming stable aggregates and increasing porosity. The result is better infiltration and drainage, less erosion and, crucially, higher water-holding capacity for plant uptake (Fig. 2). In Mediterranean olive orchards, combining compost with deficit irrigation reduced losses of soil organic carbon (SOC) by 6–38% between samplings, showing that strategic water management influences carbon sequestration. Studies indicate that for every one-percentage-point increase in SOM, water-holding capacity can rise markedly, allowing crops to withstand more days without rain or irrigation. This virtuous cycle – good irrigation leads to more SOM, which in turn leads to better water management – is the cornerstone of resilient, sustainable agriculture.

Figure 2. Comparison of soil water content by texture class and organic-matter percentage. Source: Data from

University of Minnesota Extension, 2019

From healthy soil to quality harvest: the ultimate impact on production

All of irrigation’s effects on soil—physical, chemical and biological—are not mere academic concepts; they converge and are ultimately expressed in what defines the economic viability of a farm: the quality and quantity of production. A degraded soil cannot support a high-quality harvest, regardless of other inputs.

A structurally sound, well-aerated, biologically active soil becomes an effective partner to the root system. Good structure lets roots penetrate deeply and explore larger soil volumes, increasing access to water and nutrients. Beneficial microorganisms such as mycorrhizae, effectively extend root systems, aiding the uptake of poorly mobile elements like phosphorus. Conversely, anoxic, compacted, water-logged soils restrict roots and raise the risk of diseases caused by pathogens and fungi. Saline soils hinder water uptake through osmotic stress and can trigger nutrient imbalances such as sodium–potassium antagonism. Biologically poor soils cannot efficiently convert organic fertilizers into inorganic, plant-available forms. Thus, poor irrigation management creates an environment where plants struggle to feed, even when fields are fertilized and watered.

Water stress, whether from true water shortage or from the “physiological drought” of salinity, has direct, measurable negative effects on fruit quality attributes. Yet mild, controlled water stress at specific stages under regulated deficit irrigation(RDI) can improve quality. In wine grapes, gentle stress after veraison, with a 30–50% water reduction, increases sugars (°Brix), phenolics and anthocyanins by 15–30%, improving color and aromatic profile. In olives, it can benefit oil content and organoleptic characteristics of olive oil. In cotton, it supports greater fiber length and strength. The challenge lies in applying this stress precisely; something traditional irrigation often fails to achieve.

Smart irrigation as an agroecological tool

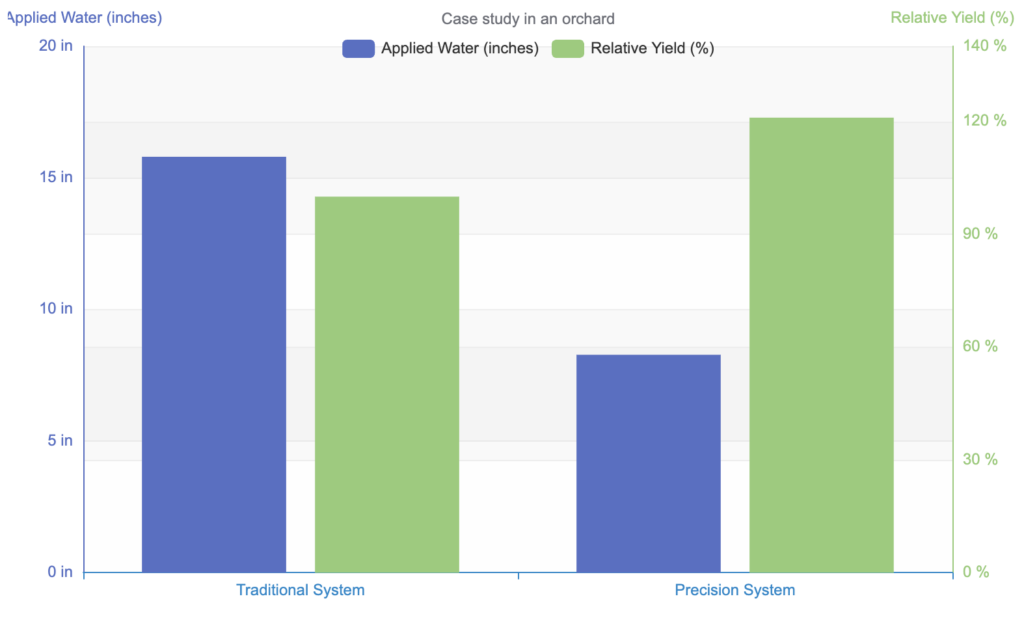

A substantive answer to these intertwined challenges is the adoption of precision agriculture. Smart irrigation is the spearhead of this approach, transforming irrigation from a blind, scheduled activity into a targeted, data-driven intervention. It answers with accuracy the fundamental questions: when, where and how much water a crop truly needs. Case studies have demonstrated its effectiveness. For example, in an orchard trial, a precision-irrigation system reduced water use by 52.4% compared with conventional management, while increasing marketable yield by 21%, leading to an impressive 232% increase in water-use efficiency (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Yield comparison: Precision irrigation vs. conventional. Source: Data from

WSU Tree Fruit Research & Extension Center, 2024

The SynField smart-farming platform implements exactly this principle, acting as an integrated brain for farm management. It incorporates real-time data from soil sensors at multiple depths in the root zone, from proprietary weather stations that capture local conditions, and from advanced crop evapotranspiration models. By analyzing these data together, SynField determines the exact water requirement and automates its application at the right time, directly into the root zone. In this way, surface runoff and erosion are minimized, compaction and nutrient leaching are avoided, and salt accumulation is effectively controlled through targeted, calculated leaching only when necessary. The result is optimized water use, protection and maintenance of a healthy, living, functional soil, and a harvest of higher and more consistent quality, safeguarding the resilience and sustainability of Greek agriculture.

Gina Athanasiou, MSc, MMus, MSc – Agronomist, Synelixis